It is important not to assume to know or understand a patient’s needs. Respectfully asking how patients want (or prefer) to be treated helps build trust and engagement. While members of an identifiable ethnic group may share common values, there is a potentially diverse range of personal preferences and opinions within any group. Be careful to avoid stereotyping. Stereotypes tend to be limiting and are often judgmental and negative.

People will conceptualize their illness and the required treatments differently, based on a number of factors including:

- cultural background

- spiritual beliefs

- prior experience

- education

A person's response to recommendations for care will be shaped by:

- their previous experience with the healthcare system

- their cultural and personal preferences and religious beliefs

- their capacity to adapt

Even within one family, there may be significant differences in acculturation. Inter-generational tension between first- and second-generation immigrants and their families is not rare.

Collapse section

A person's culture might guide behaviour in ways that are difficult for someone from a different background to understand.

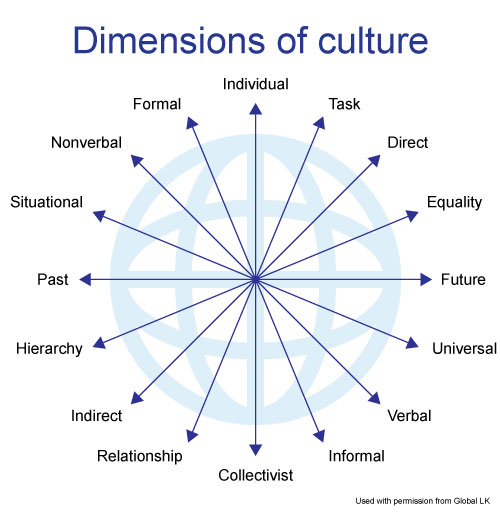

Image of the Earth with arrows originating at its center, and expanding towards the outer layer of the planet. At the end of each arrow are characteristics of culture. Opposing characteristics are found on opposite sides of the planet. They are: individual vs. collectivist, task vs. relationship, direct vs. indirect, equality vs. hierarchy, future vs. past, universal vs. situational, verbal vs. nonverbal, and informal vs. formal.

Differences between cultures can be conceptualized in terms of opposing characteristics, with individuals falling somewhere along a continuous spectrum. For example, a person with a collectivist mindset is the opposite of an individualist. Similarly, some people apply rules universally while others change the application of rules based on situational information. In some cultures, people communicate very directly while others are indirect. Finally, some cultures place a high value on hierarchy while others are more egalitarian.

Collapse section

If the golden rule states: “Treat others as you would like to be treated.”, then to be an effective cross-cultural healer, strive to apply the platinum rule: “Treat others how they would want to be treated.”

Several mnemonics illustrate how you might incorporate cultural sensitivity when communicating with patients.

One way to ensure that your patients feel heard is to explore the patient perspective using the FIFE mnemonic.

- Feelings – related to their illness, especially fears about their problem or illness

- Ideas - explanations about what is wrong, the cause for their illness, etc.

- Functioning – impact of their illness on daily activities

- Expectations – of the encounter with their physician and of the treatment

This and other mnemonics such as BATHE serve to remind us to check that patients feel heard and are able to express the impact of illness on their life and may help you to focus on cultural issues that affect the patient’s experience with illness and guide their treatment decisions.

BATHE Technique

- Background: “What’s going on in your life?”

- Affect: “How do you feel about it?” or “What has that been like for you?”

- Troubles: “What troubles (concerns, worries) you most about it?”

- Handling: “How are you handling (dealing with, coping with) it?”

- Empathy: “That must be difficult for you.”

The FIFE and BATHE mnemonics may allow you to align with the patient’s understanding of their disease condition and wishes for treatment, leading to realistic expectations and contributing to informed consent.

Collapse section

There may be times when a physician's legal and professional duty to proceed in a certain manner will be at odds with a patient's desired approach to care. Despite potential cultural differences, all physicians practising in Canada have an obligation to be truthful about all aspects of care, to provide the opportunity for informed consent, to disclose patient safety incidents (accidents in Québec), and where appropriate to discuss end-of-life issues.

Patients may have differing expectations about receiving care based on their previous experience with physicians in other contexts. Having a cross-cultural mindset – one that considers that people may view things differently and that welcomes diversity – is key in being “purposefully inclusive” and minimizing the risk of being “accidentally exclusive.”

Surfacing and managing your own biases is a good first step. Exploring diverse viewpoints and expectations with patients and colleagues alike may help you appreciate that some patients may for example, expect a more parentalistic approach to decision-making (“doctor knows best”) or may wish to have bad news be broken by family members instead of a physician. Similarly, developing an understanding of the importance and significance of truth telling for different individuals can help you design your approach to, for example, diagnoses of terminal illness and end-of-life decisions.

Similarly, relationships may be nurtured with an understanding that there are potential conflicts of values when cutlural beliefs involve strong opinions regarding the role of women, the respect of elders or an individual’s right to choose, for example. Autonomy, the right to information, truthfulness and patient-centred approaches are all central tenets of healthcare delivery in Canada. Reasonable accomodation is another key principle of practising medicine in Canada, and developing a sound understanding of these various perspectives may help foster strong doctor-patient relationships that strike an appropriate balance between treating patients like they want to be treated, and practising in accordance with the standards established by the regulatory authorities.

In Canadian healthcare, it is deemed appropriate in most situations for a physician of one gender to care for a patient of the other gender. Nevertheless, in some cultures this is deemed inappropriate and perhaps forbidden. While there is no requirement for absolute accommodation of gender-based requests to change physicians, it is both culturally sensitive and prudent to make reasonable efforts to address patient requests to be treated by a physician of the gender of their choice.

In group practices, where on-call duties include looking after the needs of the entire group’s patients and where physicians of both genders may cover call, discussing this issue with patients is preferably done at the outset of the interaction so that there is sufficient time to make alternative arrangements. Consulting available policies of the institution may also be helpful.

If urgent or emergent care is required and a physician of the requested gender is not available, providing an empathic response, acknowledging the patient’s wishes, and providing an explanation of the nature of call schedules will serve to explain why a physician of the requested gender is unavailable. Because it is always a possibility that the staff physician may need to intervene in care, it is generally inadvisable to ask residents to take on the staff physician’s role to address gender concerns.

Some patients may refuse all proposed accommodations or alternative arrangements and simply choose to be discharged against medical advice. In such circumstances, an informed refusal and discharge plan will promote safe care and help the patient make a decision.

- Outline the risks involved in refusing care.

- Suggest that the patient seek care elsewhere and identify the signs and symptoms that would suggest an evolving or worsening state as well as when to seek care.

- Offer to continue to treat the patient until alternative care becomes available.

- Document the discussion in the patient's medical record.

- You may, after discussing the risks of discharge, consider asking the patient to sign a written acknowledgement that they have been advised of the risks of discharge and are refusing further medical care.

Finding the right balance

Physicians are not obligated to provide absolute accommodation in all situations, but rather to reasonably accommodate cultural diversity.

- While physicians may recognize that professional standards vary among countries and cultures, they must be aware of and meet Canadian practice standards.

- Although it is laudable to endeavour to respect every patient's cultural background and plan care around a patient’s values, physicians need to strike the right balance between respect for culture and the provision of competent care.

Meeting your professional obligations does not mean sacrificing respect for others’ cultural traditions, beliefs, or wishes. If, for example, you receive a request to hide a diagnosis from a patient, you should explain to both the patient and the family (if applicable) why you need to inform the patient of the diagnosis. Additionally, strive to find balance by:

- Offering to tell the truth and full disclosure to mentally capable (competent) patients. Respectfully acknowledge the wishes of the family, but explain you have a legal and ethical duty to inform patients of the medical condition and options for treatment.

- Determining whether the patient understands the risks and benefits of not being fully informed about their condition. Under Canadian law, patients are entitled to make their own decisions.

- If possible, speaking to patients in private to ensure that no one is coercing them into a decision.

- Considering the involvement of a cultural broker to facilitate you mutual understanding. A cultural broker is someone who can provide cultural explanations and context to a healthcare provider in order to help them identify key issues and foster good communication.

As another example, in some cultures it is considered taboo to address issues of mental health, sexuality, HIV, cancer, or resuscitation status. Nevertheless, the practice of medicine in Canada recognizes that questions about sexual orientation and other sensitive issues are appropriate when such issues are medically relevant to establishing the diagnosis or treatment plan.

To decrease the chance of an allegation of discrimination and to provide culturally safe care:

- Provide an explanation of the reasons for potentially sensitive questions.

- Do not avoid addressing a certain aspect of a patient's health because you or your patient is culturally uncomfortable.

- Strive to educate patients in a respectful and sensitive manner when patients' beliefs may lead them to make choices that may be detrimental to health.

- Aim to provide advice to patients and make decisions about treatment based on sound medical grounds and principles.

Collapse section