At the end of 2023, 1,096 CMPA members were gastroenterologists (Type of Work 47).

The graph below compares the 10-year trends of gastroenterologists’ medico-legal experiences with those of all CMPA members.

What are the relative risks of a medico-legal case for gastroenterologists?

- Gastroenterologists, College (n=555)

- Gastroenterologists, Legal (n=179)

- All CMPA, College (n=47,991)

- All CMPA, Legal (n=13,970)

In the recent 10 years, compared to all CMPA membership, gastroenterologists had generally higher rates of College complaints 1 (p<0.05).

Gastroenterologists also had higher rate (p<0.05) of civil legal actions, especially in more recent years.

What are your risk levels regarding medico-legal cases, compared to other gastroenterologists?

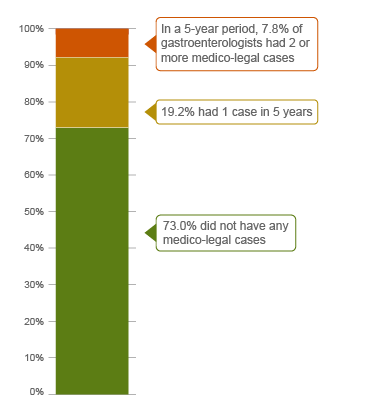

Percentage of gastroenterologists, 5-year case frequency

| No case |

73.0 |

| 1 case |

19.2 |

| 2 cases or more |

7.8 |

|

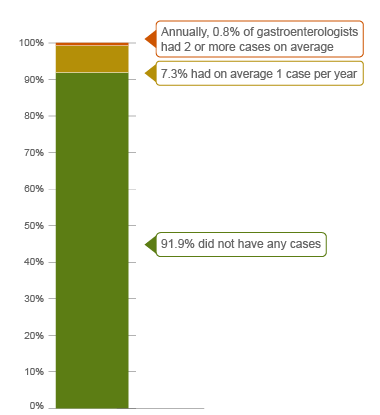

Percentage of gastroenterologists, 1-year case frequency

| No case |

91.9 |

| 1 case |

7.3 |

| 2 cases or more |

0.8 |

|

In the recent 5 years (2019 – 2023) 2, 7.8% of all gastroenterologists were named in 2 or more cases in this 5-year period. This means that these gastroenterologists had more cases than 92.2% of other gastroenterologists.

Annually, 0.8% of all gastroenterologists had on average 2 or more cases a year, and therefore had more cases than 99.2% of other gastroenterologists.

The following sections describe the findings based on the 441 civil legal cases, College, and hospital complaints involving gastroenterologists that were closed by the CMPA between 2014 and 2023.

What are the most common patient complaints and peer expert 3 criticisms? (n=441)

| Deficient assessment |

42 |

11 |

| Diagnostic error |

36 |

16 |

| Communication breakdown with the patient |

27 |

14 |

| Unprofessional manner |

24 |

5 |

| Failure to perform test or intervention |

20 |

8 |

| Inadequate monitoring or follow-up |

19 |

9 |

| Injury associated with healthcare delivery |

18 |

14 |

| Inadequate consent process |

18 |

11 |

| Poor decision-making regarding management |

11 |

2 |

| Failure to refer |

9 |

4 |

Complaints are a reflection of the patient’s perception that a problem occurred during care. These complaints are not always supported by peer expert opinion. In addition to patients’ complaints, peer experts may also have criticisms that are not part of the patients’ allegation.

What are the most frequent presenting conditions? (n=441)

- Functional disorders of the intestinal tract (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome, hemorrhoids, constipation) (65)

- Diseases of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum (e.g. GERD, gastric ulcers, esophageal obstruction) (54)

- Inflammatory bowel disease (e.g. ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease) (43)

- Malignant neoplasms of the digestive organs (38)

- Diverticular disease and polyps (36)

- Disorders of the gallbladder, biliary tract and pancreas (e.g. pancreatitis, cholelithiasis) (29)

Presenting conditions among medico-legal cases are likely representative of gastroenterologists’ practice patterns including volume of referrals for specific indication, and do not necessarily reflect high risk patient conditions.

In the 441 cases, 71 patients experienced a missed or delayed diagnosis or a misdiagnosis. For example:

- A gastroenterologist failed to diagnose a tumor of the small bowel after performing a cursory examination during a colonoscopy.

- A patient died of rectal adenocarcinoma when abnormal biopsy results were not sent to her gastroenterologist, leading to a delay in treatment.

- A gastroenterologist failed to follow up on bloodwork results which led to a delay in diagnosis of hepatitis induced cirrhosis.

In addition, 61 patients incurred an injury associated with healthcare delivery, the majority of which were perforations of the GI tract during colonoscopy or gastroscopy.

What are the top factors associated with severe patient harm 4 in medico-legal cases? (n=441)

Patient factors 5

- Age 65+

- History of or presenting with

- GI malignancy

- Obesity

- Noninfective enteritis or colitis

- Atherosclerotic heart disease

- Complication of

- Pancreatitis

- Myocardial infarction

- Intestinal perforation

Provider factors 6

- Inadequate patient assessment

- Inadequate monitoring or follow-up (e.g. failure to monitor for bleeding after removal of multiple polyps during colonoscopy)

- Failure to perform a test or intervention (e.g. digital rectal exam for patient with rectal bleeding)

- Failure to refer

System factors 6

- Excessive wait time

- Resource constraints

Team factors 6

- Communication breakdown with other physicians

Risk reduction reminders

The following risk management considerations have been identified for gastroenterologists.

- Maintain awareness of patient history, including co-morbidities and current medications. Conduct an appropriate systematic physical examination.

- Take time to pause and reflect on the differential diagnosis, being careful to consider any relevant risk factors, including comorbidities and surgical or family history. Obtain a second opinion when unsure about a diagnosis.

- For patients with continued or worsening symptoms, or those who repeatedly return with unresolved complaints despite treatment, re-evaluate the differential diagnosis, repeat the physical examination, and consider alternate diagnoses, ruling out possibilities that may be life-threatening.

- When deciding on an appropriate procedure that aligns with the patient's health goals, discuss reasonable alternative options with the patient. Carefully consider the indications for the procedure, especially in high-risk patients.

- Maintain situational awareness (i.e. keeping track of what is happening and anticipating what might need to be done) about patient condition and progress. Confirm that responsible team members appreciate the urgency of any concerns expressed about a patient's condition or progress. Use standardized terminology in verbal communication and when documenting patient status in the health record.

- Appropriately advocate on behalf of patients to solve issues that arise when limited resources pose an impediment to safe patient care; when this is not possible, establish and execute a clear contingency plan. Document any steps taken to attempt to resolve resource issues within a reasonable timeframe.

Limitations

The numbers provided in this report are based on CMPA medico-legal data. CMPA medico-legal cases represent a small portion of patient safety incidents. Many factors influence a person’s decision to pursue a case or file a complaint, and these factors vary greatly by context. Thus, while medico-legal cases can be a rich source for important themes, they cannot be considered representative of patient safety incidents overall.

Now that you know your risk…

Mitigate your medico-legal risk with CMPA resources.

- CMPA Research:

- CMPA Workshops:

- CMPA Learning:

Looking for more?

For data requests, please contact [email protected]

This report received input from Dr. Catherine Dube and Dr. Erin Kelly from the Ottawa Hospital. We appreciate their contribution to CMPA research work.

Notes

-

Physicians voluntarily report College matters to CMPA. Therefore, these cases do not represent a complete picture of all such cases in Canada.

-

It takes an average of 2-3 years for a patient safety incident to progress into a medico-legal case. As a result, newly opened cases may reflect incidents that occurred in previous years.

-

Peer experts refer to physicians who interpret and provide their opinion on clinical, scientific, or technical issues surrounding the care provided. They are typically of similar training and experience as the physicians whose care they are reviewing.

-

Severe patient harm includes death, catastrophic injuries, and major disabilities. Healthcare-related harm could arise from risk associated with an investigation, medication, or treatment. It could also result from failure in the process of patient care.

-

Patient factors include any characteristics or medical conditions that apply to the patient at the time of the medical encounter, or any events that occur during the medical encounter.

-

Based on peer expert opinions.