6 minutes

Published: April 2025

At the end of 2023, CMPA membership included 1,358 ophthalmologists (Type of Work 60).

The graph below compares the 10-year trends of ophthalmologists’ medico-legal experiences with those of all CMPA members in surgical specialties.

What are the relative risks of a medico-legal case for ophthalmologists?

- Ophalmologists, College(n=1,169)

- Ophalmologists, Legal(n=520)

- All Surgical, College(n=7,313)

- All Surgical, Legal(n=4,448)

Between 2014 and 2023, the overall rate of College complaints 1 for ophthalmologists was significantly higher than the rate of all surgical specialties (p<0.0001).

Compared to all surgical specialties, the overall rate of civil legal actions for ophthalmologists was significantly lower (p<0.0001).

What are your risk levels regarding medico-legal cases, compared to other ophthalmologists?

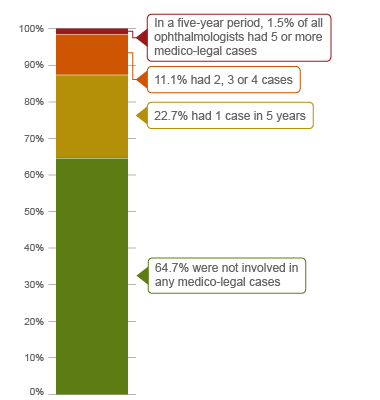

Percentage of ophalmologists, 5-year case frequency

| No case |

64.71% |

| 1 case |

22.69% |

| 2-4 cases |

11.15% |

| 5 cases or more |

1.45% |

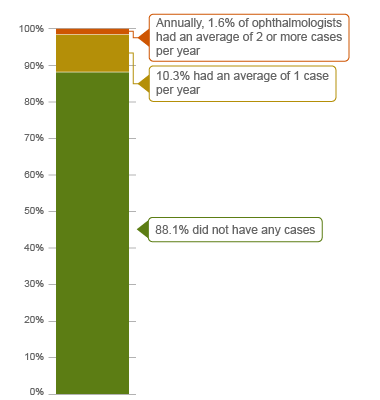

Percentage of ophalmologists, 1-year case frequency

| No case |

88.14% |

| 1 case |

10.3% |

| 2 cases or more |

1.56% |

In a 5-year period (2019 – 2023), 2 1.5% of ophthalmologists had 5 or more cases (the highest frequency of cases). Another 11.1% of all ophthalmologists were named in 2, 3 or 4 cases in this period. These ophthalmologists had more cases than 87.4% of other ophthalmologists who had either 0 or 1 case in five years. 64.7% of all ophthalmologists were not involved in any medico-legal case in 5 years.

Annually, 1.6% of ophthalmologists had an average of 2 or more cases in a year, and therefore had more cases than 98.4% of other ophthalmologists.

The following sections describe the findings based on the 536 civil legal cases, College, and hospital complaints involving ophthalmologists that were closed by the CMPA between 2019 and 2023.

What are the most common patient complaints and peer expert 3 criticisms? (n=536)

| Deficient assessment |

32.84 |

11.38 |

| Inadequate consent process |

26.12 |

16.04 |

| Communication breakdown with the patient/family |

21.46 |

12.87 |

| Unprofessional manner |

19.78 |

4.85 |

| Inadequate monitoring or follow-up |

18.84 |

5.22 |

| Diagnostic error |

18.66 |

10.26 |

| Insufficient knowledge or skill |

15.67 |

5.60 |

| Failure to perform test or intervention |

15.11 |

5.41 |

| Inadequate office procedure |

14.37 |

11.57 |

| Poor decision-making regarding management |

12.13 |

6.16 |

Complaints are driven by the perception that a problem or medical issue occurred during care. These complaints are not always supported by peer expert opinion. Peer experts may not be critical of the care provided or may have criticisms that are not part of the patient allegation.

What are the most frequent interventions for ophthalmologists with peer expert criticism? (n=536)

- Cataract extraction surgery (182)

- Therapeutic procedures for glaucoma (e.g. iridotomy/iridectomy) (64)

- Retinal surgery (e.g. laser photocoagulation, vitrectomy) (50)

- Eye pharmacotherapy by injection (e.g. Anti-VEGF) (43)

- Refractive surgery (e.g. LASIK, PRK, keratotomy) (42)

Intervention frequencies among medico-legal cases are likely representative of ophthalmologists’ practice patterns and do not necessarily reflect high-risk interventions.

The top peer expert criticisms associated with these interventions include:

- Inadequate documentation

- Inadequate consent process

- Deficient assessment

- Communication breakdown with the patient/family

- Inadequate office procedure

Out of the 536 cases, 55 patients experienced a missed diagnosis, a delayed diagnosis or a misdiagnosis. An additional 49 patients suffered injury during a procedure. Peer expert criticism on these cases include:

- Less than thorough ophthalmic assessment. For example, an ophthalmologist gave up on performing a slit lamp examination on a child patient because the patient resisted for fear of pain. Peer expert suggested the use of anesthesia to enable a complete ophthalmic examination.

- Inadequate documentation. For example, documentation that lacks detailed patient ophthalmic history, visual field testing, and/or a description of the optic nerves. Peer experts recommend thorough documentation that includes the patient's expectations, the benefits and risks of procedures, a differential diagnosis and a follow-up care plan.

- Inadequate monitoring or follow-up. For example, an ophthalmologist not arranging for regular post-operative patient follow-up to monitor intraocular pressure control resulted in severe irreversible glaucomatous optic atrophy and vision loss for the patient. Peer experts concluded that the physician’s lack of follow-up contributed to the patient’s vision loss from 20/70+ to hand motions.

- Lack of clinical knowledge or skill. For example, peer experts determined that lack of adequate clinical knowledge contributed to an ophthalmologist’s failure to adhere to national ophthalmology guidelines for annual testing to monitor Plaquenil effects. This failure resulted in the missed diagnosis of Plaquenil toxicity, ultimately leading to the patient’s vision loss.

In addition, office procedures were criticized by peer experts in 64 cases. Examples of inadequate office procedures include:

- A patient felt their appointment was rushed and that they could not discuss their concerns, the ophthalmologist examined the patient's eyelid without gloves, and they experienced an unacceptable wait time in the office. Peer experts advised the ophthalmologist to wash/sanitize their hands in front of patients prior to examination and opined the patient was seen in a timely manner.

- A patient was charged a fee for a non-insured examination (e.g. anterior chamber OCT) without explanation. Peer experts advised the ophthalmologist to ensure the patient record contains documentation of discussions related to non-insured investigations/procedures.

What are the top factors associated with moderate and severe patient harm 4 in medico-legal cases? (n=536)

Patient factors 5

- Experiencing complications of medical/surgical care:

- Cornea/external disease, e.g. keratitis, corneal edema

- Retinal conditions, e.g. retinal breaks and detachments, retinopathy, macular degeneration, endophthalmitis, vitreous opacities/hemorrhage

- Oculoplastics, e.g. lacrimal gland disorders, eyelid ptosis/entropion

- Trauma, e.g. ocular laceration and rupture

- Visual impairment/blindness

Provider factors 6

- Failure to perform a diagnostic test/therapeutic intervention, e.g. slit lamp, pharmacotherapy

- Deficient assessment, e.g. of the optic nerve

- Inadequate monitoring or follow-up

- Poor decision-making regarding whether or not to perform surgery

- Inadequate consent process, e.g. insufficient discussion of the various risks associated with a procedure

Risk reduction reminders

The following risk management considerations have been identified for ophthalmologists based on peer expert criticisms:

- Obtain an adequate history, including ophthalmic history or mechanism of injury, and conduct a comprehensive ocular examination including a dilated eye examination or test for visual acuity when appropriate. Consider whether additional diagnostic tests or consultations are necessary for the patient’s condition, being careful to consider possibilities that may be an ocular emergency. Obtain a second opinion if you are unsure of your diagnosis or to rule out a more serious condition.

- Document in the medical record the patient's history (include symptoms and co-morbidities), physical exam findings, reassessments, differential diagnoses, investigations, diagnosis, and reasoning. Include information shared with the patient, such as rationale supporting decisions about tests or treatment. Use clear and standardized language in your documentation. Ensure that information is detailed enough to enhance continuity of care.

- In obtaining informed consent, discuss and document the following:

- the diagnosis

- the nature of the proposed treatment

- its chances of success

- alternative treatments (including non-treatment and its potential consequences)

- the material and special risks associated with the proposed and alternative treatments

- In the same discussion, ensure that you address and document:

- the patient's understanding and expectations, answering any questions

- Set office standards for handling phone calls and voicemails from patients. Establish messaging for patients seeking care when the office is closed.

Limitations

The numbers provided in this report are based on CMPA medico-legal data. CMPA medico-legal cases represent a small portion of patient safety incidents. Many factors influence a person’s decision to pursue a case or file a complaint, and these factors vary greatly by context. Thus, while medico-legal cases can be a rich source for important themes, they cannot be considered representative of patient safety incidents overall.

Now that you know your risk…

Mitigate your medico-legal risk with CMPA resources.

- CMPA Research:

- CMPA eLearning:

Looking for more?

For any data request, please contact [email protected]

This report received input from Dr. Derek Waldner from the University of Calgary. We appreciate Dr. Waldner’s contribution to CMPA research.

Notes

-

Physicians voluntarily report College matters to the CMPA. Therefore, these cases do not represent a complete picture of all such cases in Canada.

-

It takes an average of 2-3 years for a patient safety incident to progress into a medico-legal case. As a result, newly opened cases may reflect incidents that occurred in previous years.

-

Peer experts refer to physicians who interpret and provide their opinion on clinical, scientific, or technical issues surrounding the care provided. They are typically of similar training and experience as the physicians whose care they are reviewing.

-

Includes moderate, severe patient harm and death. In the CMPA Research glossary, moderate patient harm is defined as symptomatic, requiring intervention or an increased length of stay, or causing permanent or temporary harm, or loss of function. Severe patient harm is defined as symptomatic, requiring life-saving intervention or major medical/surgical intervention, or resulting in a shortened life expectancy, or causing major permanent or temporary harm or loss of function.

-

Patient factors include any characteristics or medical conditions that apply to the patient at the time of the medical encounter, or any events that occur during the medical encounter.

-

Based on peer expert opinions. These include factors at provider, team and system levels. For ophthalmologists, there is no evidence for any team or system level factors in the data.