Medico-legal risk: What orthopedic surgeons need to know

Know your risk – data by clinical specialty

6 minutes

Published: May 2024

At the end of 2022, 1,525 CMPA members were orthopedic surgeons (Type of Work 94). The graph below compares the 10-year trends in orthopedic surgeons’ medico-legal experiences with those of all surgical specialties.

What are the relative risks of a medico-legal case for orthopedic surgeons?

- Orthopedic surgeons, College (n=1,258)

- Orthopedic surgeons, Legal (n=935)

- All surgical specialists, College (n=7,198)

- All surgical specialists, Legal (n=4,405)

Between 2013 and 2022, the overall rate of College complaints 1 for orthopedic surgeons was significantly higher than the rate for all surgical specialties (p = 0.0001).

Even though the rates of civil legal actions for orthopedic surgeons were closer to that of all surgical specialties since 2018, overall, orthopedic surgeons had significantly higher rates of civil legal actions (p < 0.0001) over the 10-year period.

What are your risk levels regarding medico-legal cases, compared to other orthopedic surgeons?

| %, Medico-legal case frequency, 5 years | |

|---|---|

| No case | 53.8 |

| 1 case | 27 |

| 2-4 cases | 17.5 |

| 5 cases or more | 1.7 |

| %, Medico-legal case frequency, 1 year | |

|---|---|

| No case | 84.6 |

| 1 case | 13.2 |

| 2 cases or more | 2.2 |

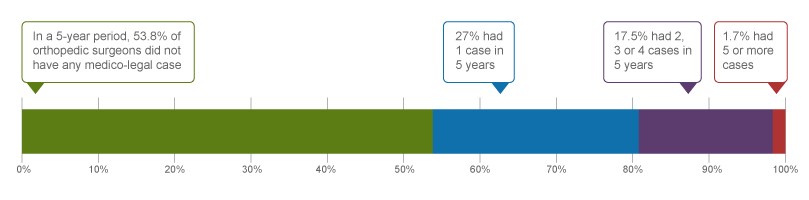

In a recent 5-year period (2018 – 2022) 2, 27.0% of orthopedic surgeons were named in 1 new medico-legal case (legal action, College or hospital complaint), 17.5% were named in 2 to 4 new cases, and another 1.7% were named in 5 or more cases.

Annually, 13.2% of orthopedic surgeons were named in 1 new medico-legal case, an additional 2.2% were named in 2 or more new cases on average across this 5-year period.

The following sections describe the findings based on the 760 civil legal cases, College, and hospital matters involving orthopedic surgeons with peer expert opinions that were closed by the CMPA between 2018 and 2022.

What are the most common patient complaints and peer expert 3 criticism? (n=760)

| Issue | %, Patient allegation | %, Peer expert criticism |

|---|---|---|

| Deficient assessment | 45 | 13 |

| Inadequate consent process | 22 | 11 |

| Diagnostic error | 20 | 13 |

| Poor decision-making regarding management | 19 | 5 |

| Inadequate monitoring or follow-up | 19 | 6 |

| Unprofessional manner | 19 | 8 |

| Failure to perform test or intervention | 18 | 11 |

| Injury associated with healthcare delivery | 17 | 9 |

| Communication breakdown with the patient | 11 | 7 |

| Insufficient knowledge or skill | 11 | 5 |

Complaints are driven by the perception that a problem or medical issue occurred during care. These complaints are not always supported by peer expert opinion. Peer experts may not be critical of the care provided, or may have criticisms that are not part of the patient allegation.

What are the most frequent interventions with peer expert criticism? (n=760)

- Total hip arthroplasty (79)

- Total knee arthroplasty (75)

- ORIF of bones of the lower limb (e.g. ankle, tibia/fibula, femur) (57)

- Fixation of the spinal vertebrae (23)

- Carpal tunnel release (13)

Intervention frequencies among medico-legal cases are likely representative of orthopedic surgeons’ practice patterns and do not necessarily reflect high-risk interventions.

Peer expert criticisms

- Inadequate consent process

- Deficient assessment

- Failure to perform test/intervention

- Failure to refer

- Poor decision-making regarding management

- Inadequate documentation

Out of the 760 cases, 100 patients experienced a diagnostic error. For example:

- A patient was left with foot drop and chronic pain when an orthopedic surgeon failed to diagnose compartment syndrome.

- An orthopedic surgeon failed to diagnose chronic regional pain syndrome after a radial nerve injury that occurred intra-operatively.

- A surgeon failed to appreciate the severity of a patient’s rotator cuff injury.

In addition, 26 patients received the wrong surgery. For example:

- A patient underwent a total hip replacement instead of a total knee replacement due to language barrier issues during the consent process.

- The surgical team failed to perform a surgical pause prior to surgery resulting in a patient undergoing surgery on the wrong knee.

What are the top factors associated with severe patient harm 4? (n=760)

Provider factors 7

- Deficient patient assessment (e.g. failure to perform neurological testing on a patient with leg numbness after spinal surgery)

- Failure to attend to patient (e.g. a surgeon relied on ED physician interpretation of diagnostic imaging, instead of examining the patient in-person, leading to surgery not being performed in time; surgeon failed to attend to patient post-operatively when complications arose)

- Mispositioning of patient

Team factors 7

- Communication breakdown with nurses

- Poor coordination of care

- Inadequate discharge instructions to patient/family

Risk reduction reminders

The following risk management considerations have been identified for orthopedic surgeons.

Pre-operative

- Maintain an awareness of the patient’s co-morbidities and surgical history. Ensure all healthcare providers in the care of the patient are appropriately involved (e.g. further specialist consultation if indicated).

- Carefully consider the indications for the procedure, especially in high-risk patients. Consider arranging for assistance for patients known to have challenging anatomy.

- Consent discussions for surgery or procedures should provide comprehensive information on material risks, benefits, alternatives, expected outcomes, and potential complications related to pre-existing conditions. Allow patients (and their family or caregivers) to ask questions. Thoroughly document the discussion in the medical record.

- Before providing medical information, assess patient's ability to understand; ensure to address language, cultural, or cognitive barriers. Use medical interpretation services as needed.

Intra-operative

- Implement standardized protocols (e.g. surgical safety checklist) to ensure interprofessional team situational awareness and improve verification practices (e.g. patient, site, procedure, and count).

- Consider the risks of intra-operative injuries during all phases of surgical care. Take precautions to protect vital structures such as nerves and vasculature, and document any efforts to visualize or protect these structures. Consider a dedicated computer screen for patient imaging.

- Consider altering technique or having a low threshold for consulting a colleague when difficulties are encountered during surgery.

Post-operative

- Provide comprehensive discharge instructions to patients or caregivers, both verbally and in writing, including postoperative instructions, wound care, medications, follow-up care, symptoms/signs to monitor, and guidance on when to seek medical attention. Provide clear information on when and who to contact in case of complications. Confirm patients’ understanding of the information being provided.

- Promptly disclose and inform patients of any complications or difficulties encountered during procedures or surgery. Discuss the implications, potential post-procedural or post-operative complications, and follow-up care with patients, ensuring open communication. Document these discussions in the medical record.

Limitations

The numbers provided in this report are based on CMPA medico-legal data. CMPA medico-legal cases represent a small portion of patient safety incidents. Many factors influence a person’s decision to pursue a case or file a complaint, and these factors vary greatly by context. Thus, while medico-legal cases can be a rich source for important themes, they cannot be considered representative of patient safety incidents overall.

Now that you know your risk…

Mitigate your medico-legal risk with CMPA resources.

- CMPA Research:

- CMPA Learning:

Questions?

For data requests, please contact datarequests@cmpa.org

Notes

-

Physicians voluntarily report College matters to the CMPA. Therefore, these cases do not represent a complete picture of all such cases in Canada.

-

It takes an average of 2-3 years for a patient safety incident to progress into a medico-legal case. As a result, newly opened cases may reflect incidents that occurred in previous years.

-

Peer experts refer to physicians who interpret and provide their opinion on clinical, scientific, or technical issues surrounding the care provided. They are typically of similar training and experience as the physicians whose care they are reviewing.

-

Severe patient harm includes death, catastrophic injuries and major disabilities. Healthcare-related harm could arise from risk associated with an investigation, medication or treatment. It could also result from failure in the process of patient care.

-

Patient factors include any characteristics or medical conditions that apply to the patient at the time of the medical encounter, or any events that occur during the medical encounter.

-

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System is used by physicians to predict a patient’s risks ahead of surgery. ASA status 4 indicates severe systemic disease that is life-threatening.

-

Based on peer expert opinions. These include factors at provider, team and system levels. For orthopedic surgeons, there is no evidence for any system level factors in the data.