6 minutes

Published: October 2024

At the end of 2022, 715 CMPA members were urologists (Type of Work 88).

The graph below compares the 10-year trends of urologists’ medico-legal experiences with those of all surgical specialties.

What are the relative risks of a medico-legal case for urologists?

- Urology, College(n=634)

- Urology, Legal(n=266)

- All surgical specialists, College(n=7,159)

- All surgical specialists, Legal(n=4,351)

Between 2013 and 2022, the overall rate of College complaints 1 for urologists was significantly higher than the rate for all surgical specialties.

During this 10-year period, the urologists’ civil legal case rates were generally lower than those of all surgical specialties.

What are your risk levels regarding medico-legal cases, compared to other urologists?

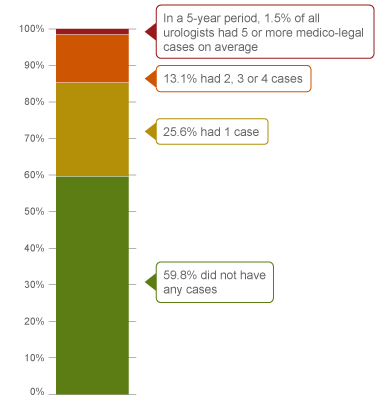

Percentage of urologists, 5-year case frequency

| No case |

59.8 |

| 1 case |

25.6 |

| 2-4 cases |

13.1 |

| 5 cases or more |

1.5 |

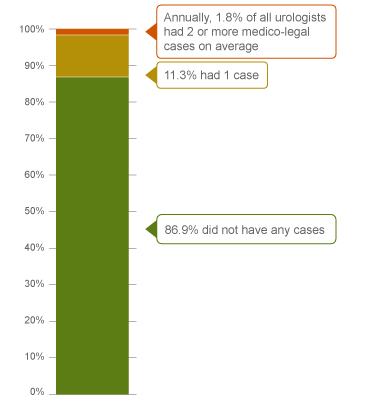

Percentage of urologists, 1-year case frequency

| No case |

86.9 |

| 1 case |

11.3 |

| 2 cases or more |

1.8 |

In a 5-year period (2019 – 2023) 2, 13.1% of all urologists were named in 2, 3 or 4 cases. This means that 13.1% of urologists had more cases than 85.4% of other urologists who had either 0 or 1 case in five years. 1.5% of urologists had 5 or more cases in this 5-year period (the highest frequency of cases).

Annually, 1.8% of urologists had an average of 2 or more cases in a year, and therefore had more cases than 98.2% of other urologists.

The following sections describe the findings based on the 625 civil legal cases, College, and hospital matters involving urologists that were closed by the CMPA between 2013 and 2022.

What are the most common patient complaints and peer expert 3 criticisms? (n=625)

| Deficient assessment |

42 |

13 |

| Diagnostic error |

37 |

25 |

| Inadequate monitoring or follow-up |

27 |

13 |

| Inadequate consent process |

24 |

14 |

| Unprofessional manner |

23 |

8 |

| Communication breakdown with the patient |

22 |

16 |

| Failure to perform test or intervention |

18 |

13 |

| Injury associated with healthcare delivery |

17 |

13 |

| Failure to refer |

8 |

4 |

| Poor decision-making regarding management |

7 |

4 |

Complaints are driven by the perception that a problem or medical issue occurred during care. These complaints are not always supported by peer expert opinion. Peer experts may not be critical of the care provided, or may have criticisms that are not part of the patient allegation.

What are the most frequent interventions with peer expert criticism? (n=625)

- Partial or radical cystectomy (33)

- Nephrectomy - laparoscopic, open and converted (27)

- Urinary tract stone extraction and destruction with or without stent insertion (24)

- Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) (17)

- Radical prostatectomy (14)

- Biopsy of the genitourinary tissues e.g. prostate, bladder, testis, lymph nodes (14)

Intervention frequencies among medico-legal cases are likely representative of urologists’ practice patterns and do not necessarily reflect high-risk interventions.

Peer expert criticisms

- Deficient assessment

- Inadequate documentation

- Delay or failure to perform test or intervention

- Inadequate consent process

- Inadequate patient monitoring or follow-up

- Insufficient knowledge/skill

Out of the 625 cases, 25% (154/625) of patients experienced a missed diagnosis, a delayed diagnosis or a misdiagnosis. For example:

- A urologist failed to follow up on abnormal cytology results, delaying the patient’s bladder cancer diagnosis, leading to metastases.

- A patient’s bladder cancer diagnosis was delayed when a urologist missed the mention of a possible bladder mass requiring ultrasound follow-up on the patient’s kidney CT report.

13% of patients suffered injuries during an intervention. For example:

- Injury to the ureters or the bladder during ureteroscopy, TURBT/TURP, or bladder lift procedures

- Injury to abdominal organs, blood vessels, and nerves during surgery

In addition, 15 patients had an accidentally retained foreign body post-intervention, and 14 underwent the wrong procedure or the procedure was performed on the wrong side.

What are the top factors associated with severe patient harm 4 in medico-legal cases? (n=625)

Patient factors 5

- ASA status 3 or above 6

- Obesity

- Presenting with cancer (e.g. cancer of prostate, kidney, bladder)

- History of cancer, major surgery, long term use of medication such as anticoagulants

Provider factors 7

- Deficient patient assessment

- Failure to perform a test or intervention

- Poor clinical decision making such as

- Failure to consider operative options (e.g. laparoscopic vs. open) when dealing with complex patients

- Failure to reconsider operative approach or seek help when intra-operative situation changes

- Misidentification of anatomy

- Deviation from administrative procedure, such as referral management and post-operative follow-up

System factors 7

- Malfunctioning equipment (e.g. laser, endoscope)

Team factors 7

- Inadequate patient handover process including poor documentation to ensure oncoming physician is aware of all issues

Risk reduction reminders

The following risk management considerations have been identified in reviewing CMPA cases involving urologists:

Pre-operative

- Maintain an awareness of the patient’s comorbidities and surgical history, and ensure all relevant providers in the care of the patient are appropriately involved (e.g. consult hematology for patients on anticoagulants).

- Ensure all test results and pre-op imaging have been reviewed and are available in the patient’s chart for review on the day of the surgery.

- Consider arranging for assistance for patients known to have challenging anatomy.

Intra-operative

- Consider altering technique or consulting a colleague when difficulties are encountered during surgery. In a timely manner, document the details of action taken to protect vital organs or structures, including surgical techniques, anatomical findings, and variants, as well as any difficulties encountered and actions taken to address the issue.

- Implement and adhere to standardized surgical safety protocols (e.g. surgical safety checklists) to ensure interdisciplinary team situational awareness and improve verification practices (e.g. patient, site, procedure, and count).

Post-operative

- Certain suboptimal outcomes reflect the inherent risks of a procedure; however, others can generally be avoided with appropriate planning and safety protocols. Ensure diligent follow-up of actual or potential complications.

- Promptly disclose and inform patients of any complications or difficulties encountered during procedures or surgery. Discuss the implications, potential post-procedural or post-operative complications, and follow-up care with patients, ensuring open communication. Confirm patients’ understanding of the information being provided. Document these discussions in the medical record.

- When appropriate and using approaches consistent with your institution’s and College’s policies and guidelines, consider advocating for patients to resolve issues that arise when limited resources (e.g. diagnostic imaging not available at night) pose an impediment to safe patient care. Document any steps you have taken to attempt to mitigate the resource issue.

Limitations

The numbers provided in this report are based on CMPA medico-legal data. CMPA medico-legal cases represent a small portion of patient safety incidents. Many factors influence a person’s decision to pursue a case or file a complaint, and these factors vary greatly by context. Thus, while medico-legal cases can be a rich source for important themes, they cannot be considered representative of patient safety incidents overall.

Now that you know your risk…

Mitigate your medico-legal risk with CMPA resources.

- CMPA Research:

- CMPA Learning:

Looking for more?

For data requests, please contact [email protected]

Notes

-

Physicians voluntarily report College matters to the CMPA. Therefore, these cases do not represent a complete picture of all such cases in Canada.

-

It takes an average of 2-3 years for a patient safety incident to progress into a medico-legal case. As a result, newly opened cases may reflect incidents that occurred in previous years.

-

Peer experts refer to physicians who interpret and provide their opinion on clinical, scientific, or technical issues surrounding the care provided. They are typically of similar training and experience as the physicians whose care they are reviewing.

-

Severe patient harm includes death, catastrophic injuries and major disabilities. Healthcare-related harm could arise from risk associated with an investigation, medication or treatment. It could also result from failure in the process of patient care.

-

Patient factors include any characteristics or medical conditions that apply to the patient at the time of the medical encounter, or any events that occur during the medical encounter.

-

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System is used by physicians to predict a patient’s risks ahead of surgery. ASA status 3 indicates severe systemic disease.

-

Based on peer expert opinions.